Categories

Important Concepts

Explore public health and scientific concepts below.

Experimental vs. Observational Studies

Studies are what epidemiologists call investigations. They are done to measure disease occurrence—in terms of incidence and/or prevalence and measures of them like risk and rate. Investigations are also done to measure the relationship between health factors and outcomes—in terms of associations and measures of them like risk-and rate-ratios.

There are two main types of epidemiological study designs: Experimental studies and observational studies. Both involve collecting and analyzing data to understand the relationships between health factors and outcomes.

Experimental Studies

Researchers use experimental studies when they want to establish a causal link between two or more factors.

- The researchers running the study have control over a variable (exposure, treatment, or factor) of interest.

- Experimental studies randomly assign study participants to comparison groups to determine the causal effect of an exposure, treatment, or factor on an outcome of interest.

- These studies reflect ideal conditions in controlled environments. They can be used to establish causality, where outcomes can be attributed to the variable of interest being manipulated.

Observational Studies

Researchers use observational studies when they want to identify an association between two or more factors. Sometimes this is done to increase understanding of whether a link is causal.

- In observational studies, the researchers conducting the study do not have, or have very limited, control over variables of interest. For example, exposures, treatments, or factors.

- Observational studies do not randomly assign study participants to comparison groups. They allow researchers to observe (not manipulate) variables to determine associations between those variables and outcomes of interest.

Specific Experimental and Observational Epidemiological Study Designs

One of the main goals of (etiologic) epidemiology is to answer the question: Did this exposure cause that health outcome? For example: does smoking cause lung cancer?

The best way to answer this question would be to compare the same person in two identical worlds where the exposure is the only difference:

- One where they were exposed. For example: they are a smoker

- One where they were not exposed. For example: they are not a smoker.

This is called the counterfactual — the “what if” world that didn’t or can’t actually happen.

Of course, we can’t split one person into two versions of themselves to see both outcomes at the same time. This is why we need study designs that get us as close as possible to that ideal comparison.

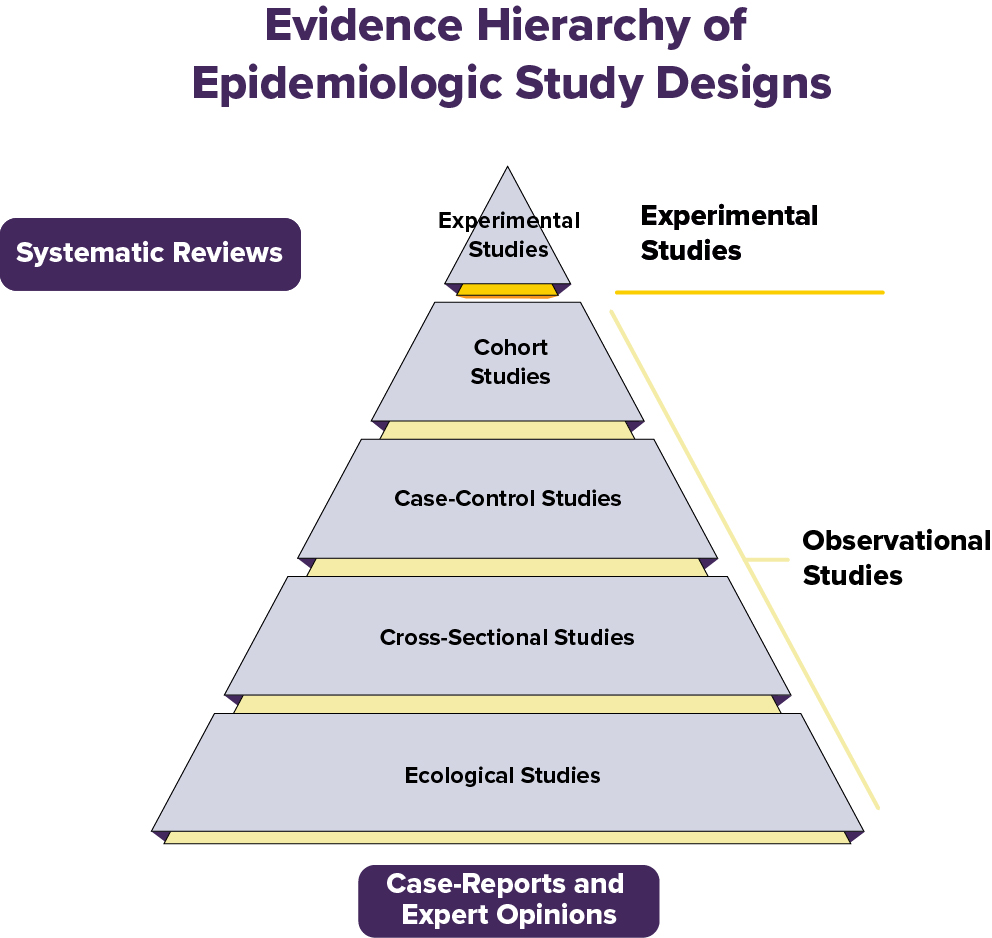

The Hierarchy of Evidence in Study Designs

Not all studies are equally strong when it comes to proving that a given exposure causes an outcome. In epidemiology and medicine, we think about a “hierarchy of evidence” — a pyramid that shows which study designs give us more dependable answers.

Experimental studies (the top of the pyramid) can establish a causal relationship between an exposure and outcome. All other study designs are observational and can only establish an association between an exposure and outcome.

We will describe several epidemiological study designs below.

Experimental Studies:

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)

- Participants are randomly assigned to groups--for example, treatment vs. placebo. They are unaware of which group they are assigned to. This means they are blinded.

- Randomization helps remove other factors that could impact the study results. This makes it easier to tell if the treatment really works.

Example: A group of volunteers with cancer is randomly assigned to take a new medicine or a placebo. Researchers assess whose cancer has improved.

The randomized controlled trial is often called the gold standard because:

- Randomizing participants into exposure groups balances out known and unknown factors between groups.

- Blinding reduces bias. Blinding is not telling participants and/or research staff who is in which exposure group, when possible.

- The comparison between groups makes it easier to see if the treatment or exposure really caused the outcome.

Still, no study is perfect—randomized controlled trials can be expensive and time-consuming. Also, they are not always ethical or appropriate. For example, we might suspect a certain food additive is harmful and want to confirm via research. It would not be ethical to intentionally assign some people to consume the additive. That’s why all study types have a role, depending on the research question.

Observational Studies:

Cohort Studies

- Evaluate groups of people who were exposed or unexposed to a potential risk factor over time to see who develops a certain outcome.

- Epidemiologists compare the occurrence of the outcome between the exposed and unexposed group using measures like the risk-ratio or rate-ratio. These measures help epidemiologists determine the strength of the association between the risk factor and outcome.

- Good for studying risk factors, especially rare ones. But cohort studies may take a long time to conduct. They can also be affected by biases including confounding.

Example: A group of people who smoke and a group of people who do not smoke are followed for 20 years to see how many in each group develop lung cancer.

Case-Control Studies

- Assess people who already have the health condition or outcome (cases) and people without it (controls). Ask about their past exposure history.

- Useful for rare outcomes, but more prone to recall bias. This is when people incorrectly remember or report past events.

Example: Researchers start with people who already have lung cancer (cases) and compare their past smoking history with people who don’t have lung cancer (controls).

Cross-Sectional Studies

- Evaluate data from a single point in time (“a snapshot”).

- Helpful for finding associations but can’t show cause and effect, because we do not know if the cause (exposure) happened before or after the effect (outcome).

Example: A survey asks thousands of people at one point in time whether they currently smoke and whether they currently have lung cancer.

Cross-Sectional Studies

- Evaluate data from a single point in time --“a snapshot.”

- Helpful for finding associations but can’t show cause and effect. Why? Because we do not know if the cause (exposure) happened before or after the effect (outcome).

Example: A survey asks thousands of people whether they smoke and whether they have lung cancer.

Ecological Studies

- Compare groups or populations (not individuals) — for example, country-level smoking rates and lung cancer rates.

- Quick and cheap, but weak because group-level trends don’t always apply to individuals. This is called ecological fallacy.

Example: Scientists compare average national smoking rates with national lung cancer death rates across different countries.

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses:

- Includes results from a group of studies to give the most complete picture (i.e., combine the available evidence or data).

- Can be strong because they may increase the confidence in findings (by increasing precision and reducing bias) by assessing and pooling many studies and their data.

- Systematic reviews are a descriptive summary of patterns and findings from a group of research studies. Meta-analyses combine data from separate, similar studies to produce overall statistical results.

Example: Researchers gather all published papers on whether smoking is associated with lung cancer, then summarize the results across all studies.